When North London Collegiate School had been going for 28 years, Headmistress Frances Buss declared that 4th April, Founder’s Day, should ‘always be a day of importance in the year’. She intended this to be an opportunity to open the school’s doors to friends from the outside world. In truth, the date moves a little with the end of the Spring Term, but the principle of Founder’s Day is alive and well, and it is our pleasure today to celebrate Miss Buss, her vision for young women’s education and her inspirational leadership.

These days we pick a theme for Founder’s Day, and this year it is the power of connections. For Miss Buss certainly had the ability to make great things happen by seizing and amplifying the serendipitous connections that life threw in her path. I think she had the political instincts of a hustler: not just an educational pioneer, but a clever operator too. As her protégée, Sophie Bryant, the school’s second Headmistress, remarked: Miss Buss ‘had her eye always on the larger issues’. She understood perfectly the role that NLCS could play in the outside world, and the role the outside world could play for NLCS.

This year, as the independent sector faces one of its most serious political challenges yet, I want to reflect on the role that NLCS has played as a shaper of thought, as a persuasive power and as an architect of reform. It is about the ability of NLCS to shape and change opinion, and to use connections to make change.

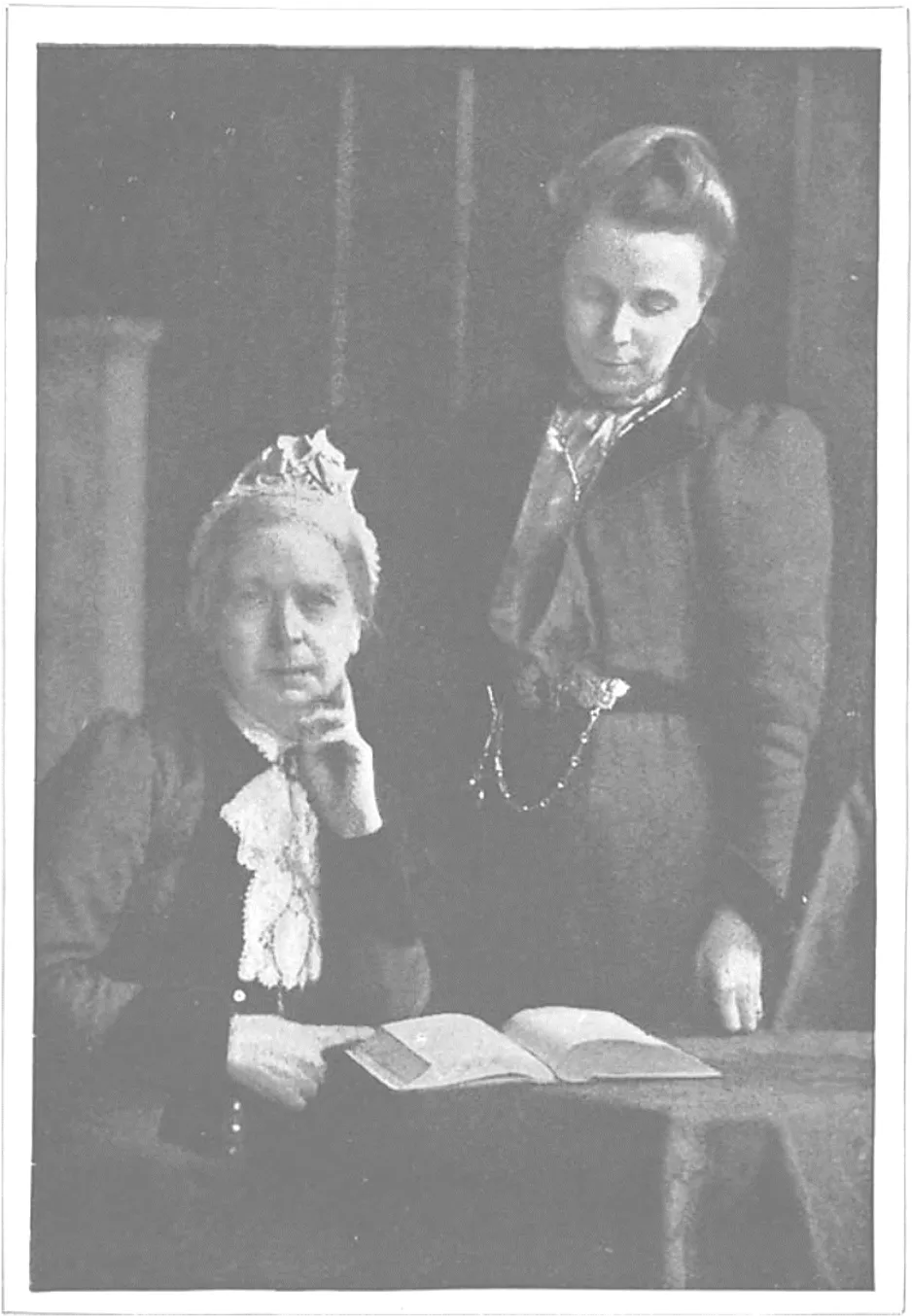

Miss Buss and Dr Bryant

NLCS has always taken up space in the world. It has always been a school of influence and impact. As well as being Headmistress of NLCS, Frances Buss also set up Camden School for Girls in 1873, was a governor at University College London, served on the Councils of Cheltenham Ladies’ College, the Church Schools Company, the Royal Drawing College, the London School of Medicine, helped to found the Cambridge Training College for Teachers, and even found time to sit on the Women’s Branch of Swanley Horticultural College. Frances Buss was a woman who understood long before the advent of all-female networking groups the power of professional connections.

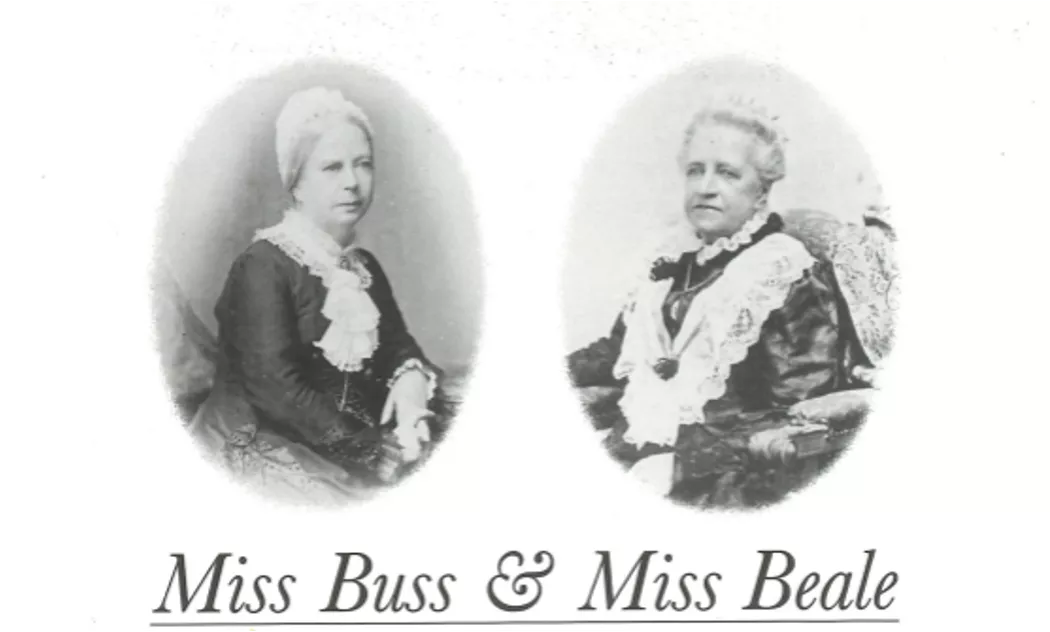

Earlier this academic year, I received an email from the Association of School and College Leaders asking if they might host a drinks reception at NLCS to celebrate their 150th anniversary. ASCL today is a significant body in the educational world as the biggest union for headteachers. Its President is someone whose voice holds sway in the Department for Education. But its inception was charmingly casual, born again out of one of Miss Buss’s connections. In a letter of 1874 Miss Buss remarks in an almost off-hand manner that her friend, Miss Beale, of Cheltenham Ladies’ College, called on her to opine that she and Miss Buss ought to form an Association of Headmistresses.

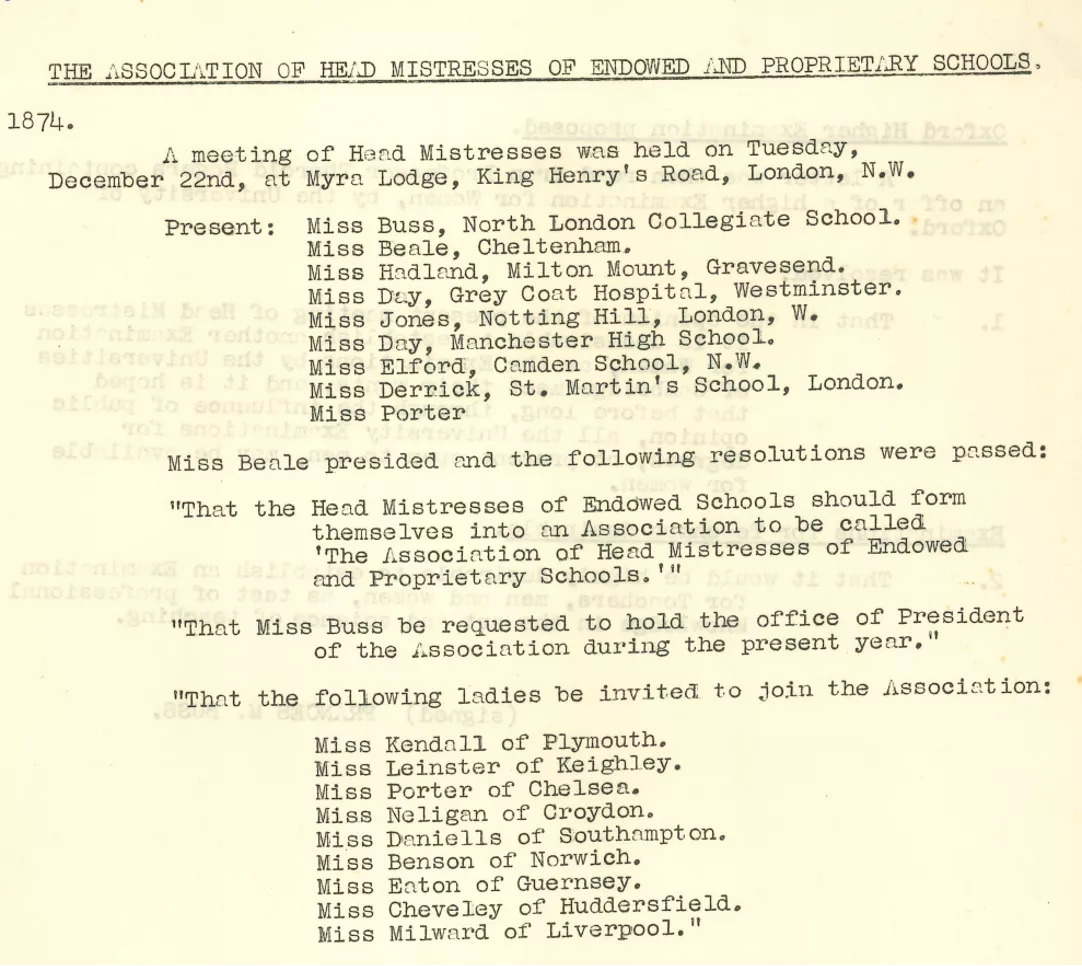

The Association of Head Mistresses, 1874.

And so it was that the very first meeting of ASCL (then called the Association of Headmistresses) was held in the drawing room of Frances Buss’s own home, Myra Lodge, in Primrose Hill on 22nd December 1874. She was the first President of the Association and Sophie Bryant, her successor as Headmistress, was the second. Dame Kitty Anderson in the 1950s was another NLCS Headmistress to take the helm of the Association.

The Association set out to provide Headmistresses with the same professional support as Headmasters. The agenda of their first meeting reveals the sexism that even these august scions of female education experienced. Unlike their male counterparts in Britain’s historic public schools, the first Headmistresses had to contend with rather over-involved Governing Bodies. The first resolution passed by the Association is revealing: the Headmistresses demanded full control over the appointment of their staff, the power to exclude a pupil if her conduct was insubordinate or unsatisfactory or her influence over her peers objectionable, and to exercise full autonomy over the choice of curriculum books and teaching methods.

Although these two women were in direct competition as heads of Britain’s most famous girls’ schools, neither saw the other as a rival but rather as a fellow-worker in a great cause, the advancement of women’s education. Together, they played a part in nearly every educational reform we now take for granted. They realised that collaborative connection rather than competition was what would deliver their legacy – and what a legacy it is.

Miss Buss & Miss Beale