Thinking

Out of the Depths of Darkness ~ Jacob’s Room, 1922

On what she noted was the “first day of winter time” in October 1920, Woolf began her diary entry by dramatizing her particularly low mood: “Why is life so tragic; so like a little strip of pavement over an abyss. I look down; I feel giddy; I wonder how I am ever to walk to the end.” Belonging to what she designated the post-war “tragic” generation, she recognised in 1920 that “unhappiness is everywhere” as the newspaper placards demonstrated every day. Yet, despite her application of the same metaphor about the strip of pavement to the essay she had just penned in recognition of how fragile art is in the face of cataclysmic loss, this October diary entry concludes with her promise to keep on at her next work, Jacob’s Room, the writing of which she says will “revive” her “fibres”.

A year and half on, Woolf recounts how when reading its manuscript, her husband Leonard could see how Jacob’s Room was “unlike any other novel”. Notably, it would be the first novel their homegrown Hogarth press would publish and the first two editions made a handsome profit of £42. 4 S. 6 D. Her fellow modernists, T S Eliot and E M Forster, also told her that the work was considerably more than just an experiment, amounting, as they saw it, to a template for a new type of prose-fiction. While never “blind to its imperfections” as she said – and certainly, I am not claiming here that it is anything like as monumental as the key 1922 works of Ulysses and The Wasteland – for Woolf, this essentially non-realist, poetic novel marked a very real arrival at the narrative “looseness and lightness” she was seeking.

Quite purposefully working for a new voice distinct from that of the largely conventional two novels she had already published, Woolf also wanted to refute Arnold Bennett who in late 1920 had circulated essays arguing that men were cleverer and more creative than women. It is surely fitting then, in this centenary year, that we celebrate a work by the century’s greatest female writer who along with Joyce and Eliot, had had the courage to “go out into the desert and peer about, like devoted scapegoats, for some sign of a path”. Its achievement is the more remarkable when we remember that around the time of writing Jacob’s Room, Woolf was suffering acutely in her mental and physical health, inducing the belief that life would be short, and certainly, not long enough to write the masterpieces she would go on to produce with Mrs Dalloway, TTL and The Waves, great modernist works that owe their being to the innovation of Jacob’s Room.

Rather than comprehensively follow the new technical path first trodden by this novel, instead, I aim to illuminate Leonard Woolf’s aside that “the people [in it] are ghosts”. This is of course quite literally true of the main character whose surname of Flanders underlines how he represents the thousands of young men lost to Britain in the First World War. Indeed, the question continually posed by the novel – “what can this sorrow be” – has a very real answer in the shape of the sunken battleships in which “a dozen young men in the prime of life descend with composed faces into the depths of the sea”.

Certainly, in one childhood scene, Jacob already seems to be coming up from the underworld: “There he stood pale, come out of the depths of darkness, in the hot room, blinking in the light”. Although it is not recorded until the quiet pages that conclude the novel – and then only obliquely – Jacob’s death is often foreshadowed, as it is right from the start when his mother calls out for her lost son. And certainly, such prefiguring of the unrealised potential of a young man who is visualised walking in the “springy air of May” at one point, is registered through the frequent signifiers of loss that punctuate the text.

While working to eschew the autobiography form, Jacob’s Room famously elegises Woolf’s brother Thoby who had died from typhoid in 1906, and in fact, around the time of writing the novel, Woolf records her “dumb rage still at his not being with us always” – a feeling that emanates right the way from Mrs Flanders’ very first cries to the persistent sense of absence at the heart of the novel as encapsulated in its final lines when his mother asks of a pair of Jacob’s old shoes, “What am I to do with these?” Equally, such absence is successfully evoked throughout the novel by the surprising retention of an omniscient narrator of sorts who is able to testify to the sheer look of loss in an uninhabited room, something no character would be able to witness or intuit. Prefigured through such an objective view of Jacob’s room – “listless is the air in the empty room, just swelling the curtain…”, the advantage of retaining this narrator is that it can raise epistemological questions. Further, it is the elegy form – the purpose of which is to remember, commemorate and lament – that shapes Woolf’s new enquiry into how a novelist should characterize, and, at the more psychoanalytical level, how a person knows another person – one of the central aesthetic and philosophical questions of Woolf’s work from here on. It is not insignificant that she had for a father, the compiler of the Dictionary of National Biography.

Writers, Woolf remarks, have historically “addressed themselves to the task of reaching, touching, penetrating the individual heart” and for all its lacunae, as this novel demonstrates, she always does this most searingly through the elegy form. Accompanying the democracy, anonymity and neutrality of multiple view-points in this knowing process, are the elegiac fragments, snippets of dialogue, sudden and fleeting visions and vignettes that essentially comprise the entire material of Jacob’s Room then. Such snatches which themselves mirror a mourner’s own self-conscious attempts to recall an especially prematurely lost life, would, in all their contingency, go on to constitute one of Woolf’s distinguishing characterization methods. For certainly, real lives are, the narrator extrapolates, like the newly fashionable paper flowers that opened in water but still prove to have “foundered”. While avoiding any sustained sense of omniscience – after all, as she said, it is no use trying to summarise a character since “The human soul orientates itself afresh every now and then” – the novel’s gentle, if persistent, enquiring, voice keeps querying its own art, before concluding that “It seems that a profound, impartial, and absolutely just opinion of our fellow-creatures is utterly unknown”.

A reflective hall of narrative mirrors is set up at the very start of the novel with a portrait of an artist, Mr Steele in his Panama hat, wondering how to define with just the right lines of his paintbrush, Jacob’s mother who is herself breaking off from writing a letter. The work’s many window frames, snatched views and references to sight, delineate its self-reflexive dimension. For instance, initiating the grief that is to reverberate through the finely-wrought poetry of each page, Woolf has the widowed Mrs Flanders envision a provisional and shape-shifting world. “the entire bay quivered; the lighthouse wobbled” through tears that would have had their origin in those of Virginia Stephens herself, the perennially grieving girl and young woman.

Further, it is the sceptical quality of this self-reflexive voice that renders this elegiac novel more postmodern in its purposeful muddle of fragments than Woolf’s subsequent elegiac works, TTL and The Waves, which are comprised of distinctly longer and more uninterrupted strings of memories. It is of course the novel’s cataclysmic, if indirect, intervention of history – the First World War, – that gives this elegy the particularly provisional and contradictory quality more usually found after the 2nd World War, the horrors of which suggested that there could actually BE no literary response. Long before that, Woolf’s great understanding as first articulated in this novel, is that all our efforts to relate, to narrate and to tell, largely always fail in the face of death and tragic loss. As full of references to the act of writing and reading as it is to vision, the work holds that we are all doomed to “to write letters, send voices, which fall upon the tea table, fade upon the passage”. Accordingly, the narrator goes on to remark in one of the novel’s philosophical passages, that although “life must have been understood for hundreds of years yet no one has left any adequate account of it. The streets of London have their map, but our passions are uncharted.” And while one of her great contributions to literary modernism is her novel’s cinematic depictions of the city, so too will her efforts to map our psychology through engagement with the quotidien – one of the novel’s main ways of memorializing its hero.

One characteristic of elegy of course is that such remembering involves celebrating and mourning at the same time. And like one of the novel’s myriad of characters’ reflective minds “looking from hill to sea”, the novel is equally poised between gloom and laughter. Often, Woolf’s ebullient, yet at the same time, perplexed, voice seems to match that of the novel’s thrush “trilling out into the warm air a flutter of jubilation, but fear seemed to spur him…as if he too were anxious with such joy at his heart”. Certainly, there are always intimations of mortality threaded into Woolf’s prose that keeps cutting into the innocence and beauty in the same way as the turning and rattling mowing machine “creaked – creaked – and creaked again” under Jacob’s actual bedroom window. While reading the novel, it is difficult too not to hear Shakespeare’s sonnet 60 in which “time that gave doth now his gift confound”, and with her lawnmower – an auditory worrier of mortality – Woolf concurs with Shakespeare that “nothing stands but for his scythe to mow”. As Woolf’s narrator more prosaically puts the problem faced by all elegists: “there has never been any explanation of the ebb and flow in our veins – of happiness and unhappiness.”

It is the novel’s particularly sensory writing however that evokes such alternative emotions from the reader in response to the tragi-comic world in which Woolf places her characters. Certainly, depiction of the natural world seems to have been one of her aims as she recorded in her diary of April 10th 1920 when she wrote *** “I’m planning to begin Jacob’s Room next week with luck. (That’s the first time I’ve written that.) It’s the spring I have it [in] my mind to describe.” And she goes on in her description to detail how the year appears to have escaped winter: there is “never any of that iron blackness of the chestnut trunks – always something soft & tinted. In fact, we’ve skipped a winter… So I hardly notice that chestnuts are out – the little parasols spread on our window tree; & the churchyard grass running over the old tombstones like green water…..” Yet, as this final image of the tombstones also makes clear, the intrusive narrative voice of Jacob’s Room holds that all “Loveliness is infernally sad” since, as the novel announces repeatedly, all efforts to bury signs of winter are misplaced alongside the sure and Romantic knowledge that nature has mortality factored in to it, as it seems to register.

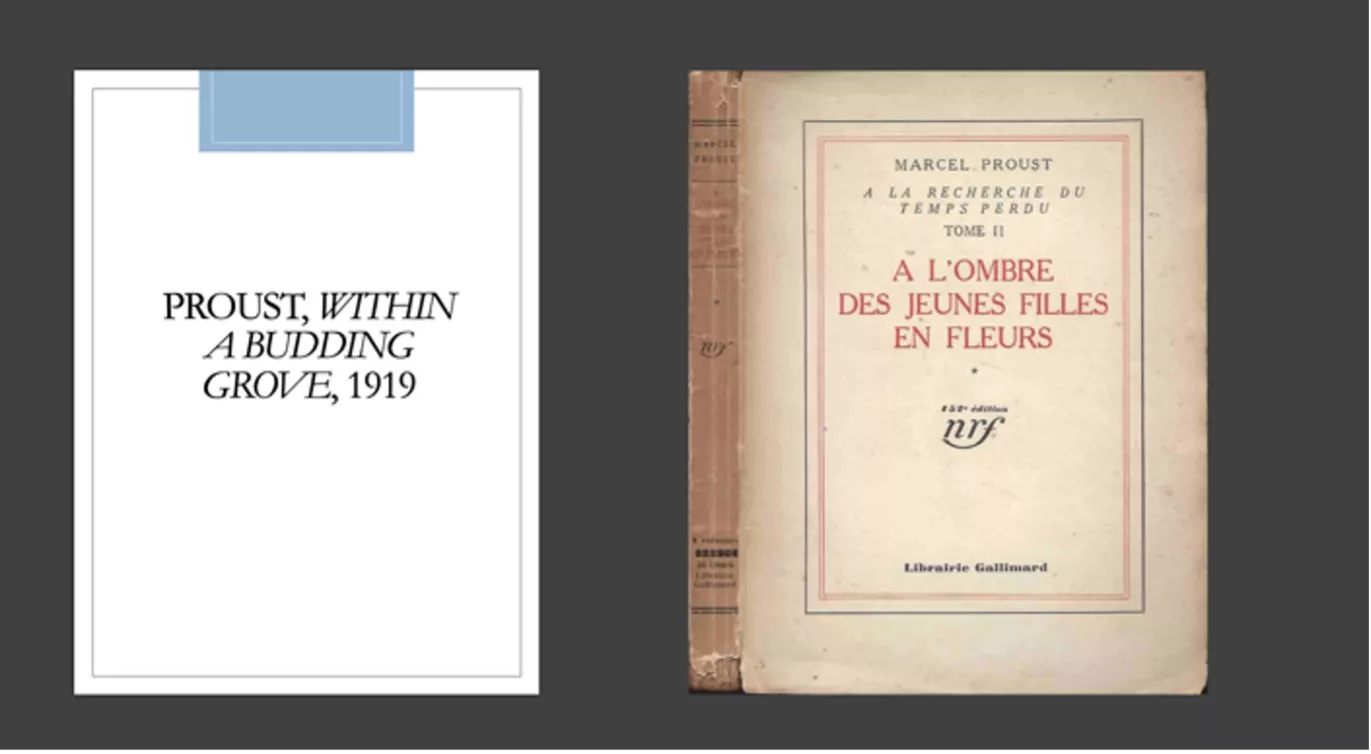

One self-reflexive and sensuous image towards the end of the novel is of great sailing ships as backdrop to Jacob’s stay in the cosmopolitan and impersonal melting pot of Athens, and such ships become the signifiers of “steamers, resounding like gigantic tuning-forks” that “state the old fact – how there is a sea coldly, greenly, swaying outside…..”. Certainly, the novel in which the eponymous hero watches a ship “sail from one corner of the window-frame to the other”, as if charting his own short life, is always attuned to the dual presence of eternity and mortality as figured by the continual ebb and flow of the waves. Again, Woolf seems to have taken her cue from Shakespeare’s sonnet which symbolises the erosion of time in the waves that “make towards the pebbl’d shore”. However, I would also think that Marcel Proust’s painstakingly poetic evocations of the waves turning on the Normandy coast in Within a Budding Grove (vol II) – a work Woolf was reading admiringly at the time – have found their way into this particularly dream-like, maritime and liminal work.

Indeed, the influence of Proust who led the way in interleaving fleeting and lost time in his great novelistic search of memory, can be felt on every page in a novel in which time is recorded progressing across the sea until the dark slapping of the waves “with an appalling solemnity” reaches the boats. Surrounded on all sides by glimpses of the changing seascape in the self-reflexive and transient metaphor for instance, of “an exhibition of Japanese colour-prints”, Proust’s young narrator realises such sights can only ever be temporary “pictures” below which lie “the sad desolation of the beach…” Similarly, Woolf’s narrator traces the kaleidoscope of colours passing over the sky, “leaving wedges of apple-green and plates of pale yellow”. Coming from Mrs Flanders’ already grieving perspective, such detailed transcription of the shifting light on the moving waves already conveys just such a Proustian seam of ambivalence: “this black mutability, against this blazing sunset, this astonishing agitation and vitality of colour, which stirred Betty Flanders and made her think of responsibility and danger.” Prefiguring great, global loss, the innocuous sound of “dashes of rain” and the minute tap of a leaf on the window mutate into the powerfully ominous fact that “There was a hurricane out at sea.” Indeed, this simple sentence gives rise in the next section to waves so cosmically destructive that they “raced over the Atlantic, jerking the stars above the ships this way and that.” Alongside the deliberative patterning of Woolf’s natural imagery, one of the structural successes of the novel is how it is bookended by sea pictures – first by this storm in Jacob’s early boyhood and then, by the same sea now merged with the sound of the guns travelling over the Atlantic to Cornwall from the French battlefields as a signifier of Jacob’s death.

Notwithstanding then, the text’s exquisite moments of sensory ambiguity such as the smell of the camphor for preserving Jacob’s butterflies mingling with the smell of the seaweed continuing to erode them, the sea nearly always represents the tide of death in the novel. Even when celebrating the sea – “and above all, the white sand bays with the waves breaking unseen by anyone, rose to heaven in a kind of ecstasy” – Woolf is careful to quickly shift our focus up to “a wreath of smoke above”, picturing it like “a mourning emblem”.

In fact, in a novel that is so innovative in the manipulation of time – as influenced by cinema – a composite scene of the times and places Jacob chases and captures butterflies and moths – which Woolf’s brother Thoby also collected as a boy – is itself a poignant parallel for the act of elegising and memorialising. Here, Woolf’s cinematic lens bringing disparate places and times together in a tribute to Thoby’s childhood comes into its own here in a couple of pages which range particularly widely over various sites. Yet, all the while Jacob is capturing these butterflies, the text juxtaposes the family’s maid catching “the death’s head moth in his home’s kitchen.” Another of the evenings upon which Jacob triumphantly found a butterfly is darkened by one of Woolf’s autobiographical memories – the sound of a tree falling at night. As one such pivotal ‘moment of being’ which are invariably epiphanies of mortality for Woolf, here Mrs Flanders prefigures the death of her son when she “thought something dreadful had happened.”

Alongside the butterfly, the novel makes use of the motif of a sheep’s jaw and time-worn skull as found by Jacob, a young tragic Hamlet who was of course modelled on the sibling who was a particularly keen scholar of Shakespeare. “Clean, white, wind-swept, sand-rubbed, a more unpolluted piece of bone” the narrator insists “existed nowhere on the coast of Cornwall”. Several times subsequently, the narrative draws attention to what it terms the “skeleton behind the flesh” which not only foreshadows the end of Jacob’s life, but in recalling the gravedigging scene in Hamlet, foregrounds the philosophical seam of a novel that queries death and existence just as much as the Dane does.

In 1867 Matthew Arnold had figured the Victorian search for meaning amidst a Godless universe in the “grating roar/of pebbles” coming in and out with an “eternal note of sadness “on ‘Dover Beach’, a text also lying at the heart of Jacob’s Room, and correspondingly, the novel is punctuated at several points by a “doleful lamentation” breaking in, most searingly, at particularly celebratory times. For instance, a snow-bound countryside lit by a man carrying a lantern, suddenly, and inexplicably, becomes a tragic scene when “later there was a mournful cry….the dark shut down behind it.” In another particularly elegiac passage set at the Roman Fort just before the novel ends, Mrs Flanders is ruminating about time, and about how it feels as though all the dead are present at night. Although she seems comforted by how “The moor accepted everything” – it tucks her fallen brooch safely in alongside Roman skeletons – persistent and stabbing questions of “what? And why?” break in to her thoughts as they do the text.

Crucially, Mrs Flanders’ revelations at The Roman Fort take place on the eve of Jacob’s trip to Greece which is where Woolf’s brother Thoby picked up the typhoid infection from which he would die on his return to London. Epiphanic to Thoby whose letters attest to a prescient sense of ecstasy in all that he discovered, Woolf’s trip with Thoby to the Peloponnese was also obviously one of the most important voyages of her life about which she wrote at length in her first diary. Notably, Woolf’s life-long immersion in the Classics was ignited by Thoby who inspired her to learn Greek at the age of 15.

Later, at Thoby’s death, Woolf must surely have been comforted by ascertaining what Arnold had already thought of Sophocles’ response to the ebb and flow of time as charted by the waves: Sophocles, according to Arnold, long ago Heard it on the Ægean, and it brought Into his mind the turbid ebb and flow Of human misery.

An actual Greek lamentation is recorded by Woolf in one entry of her Greek diary when she recalls how “a band of wailing women are signing beneath my window” about which she goes on to ask, “Do they lament the nation’s fall, or some private woe…..” And so, the open-ended question posed by Sophocles and Arnold, also becomes Woolf’s in Jacob’s Room which asks whether such misery should be accepted, or transcended. At one level, in the face of such great loss perpetrated by “ignorant armies” – figured by Woolf as “the old pageant of armies drawn out in bitter array upon the plain” – the Greek section of Jacob’s Room finds consolation, harking back perhaps to an essay written soon after Thoby’s death which states Greeks face up to “a sadness at the back of life….and it is to the Greeks that we turn when we are sick of the vagueness and of the confusion, of Christianity and its consolations, of our age”.

Even before it reaches Greece, the novel both seeks and envisions a sacredness and sense of permanence in the timelessness of place. The chapel of King’s College ***where Jacob studies “burns steadily”, for instance, making the narrator declare with Shakespearean rhetoric how “neither snow, nor greenery, winter nor summer has power over that old stained glass.” Equally, the particularly arresting British Library scene in which Jacob is transcribing Marlowe has the narrator ask “is learning eternal”? In the hungry intellect of Jacob, the elegy locates compensatory and comforting icons: “For after all Plato continues imperturbably. And Hamlet utters his soliloquy. And there the Elgin Marbles lie, all night long, old Jones’s lantern sometimes recalling Ulysses, or a horse’s head….” Indeed, the obsession Fanny has for Jacob will lead her to the busts in the British Museum, and namely, to one of Ulysses. In a London novel in which the city acts as a barometer of time – from Notting Hill to Clerkenwell, “the flamingo hours fluttered softly through the sky” – several passages take the burgeoning city of London back in time through a retrospective cinematic lens, seeking, along the way, a sense of timelessness that can be located in what was once natural landscape. Such perception of the vast capaciousness held by landscape, seems to have been inspired by Woolf’s sights along the Aegean: “where does the place begin – where stop – what does it not gather on its way? There never was a sight, I think, less manageable; it travels through all the chambers of the brain, wakes odd memories and imaginations; forecasts a remote future; retells a remote past”. Accordingly, it is in the section of Jacob’s travels through Greece – the summation of both Thoby and Jacob’s lives – that Woolf most anxiously pits the redemption of lasting beauty against the ravages of time. A similar “Piety and peace” are attributes that the narrator had earlier often ascribed to the Cornish Coast. The narrator seems to know that the pictures she draws of the Scilly Isles “as if directly pointed at by a golden finger issuing from a cloud….shake the very foundations of scepticism and lead[s] to jokes about God”. Her diary of 1906 records how coming along the coast to Athens made Woolf feel how “the whole place seemed chiselled like a statue”. Equally, the stones of the Parthenon – which she described in her diary as “immortal” and “too great for the mind to grasp” were, she said “of serene immutability, here is a type that is enduring as the earth, nay will outlast all tangible things”.

Yet as her diaries again record – and as Lyndall Gordon points out – however much she wanted to enter into the spirit of Greece, and however much structural motifs of music and shafts of light falling on places in the resulting novel, might challenge atheism, Woolf recognised that her idea of the permanence of ‘Greekness’ might be illusory. Instead, she must make do with a tortuous balance between loss and gain – the effervescence” on the one hand, and the “treeless land” on the other; the novel paradoxically locates a tenuous sense of immanence not in the plenitude of place, but in its emptiness. For instance, when walking up to Mount Olympus, Jacob decides “bare places…suit us better than cities”, and certainly, such depiction of empty landscape – a “ clean-cut, a treeless land”, an ancient place of profound yet beautiful vacancy, is one answer to the great losses of the first world war.

As Woolf wrote in her diary, she and Thoby – like Jacob after them – found the Grecian landscape to be chiselled and contoured with palpable marks “The extreme definiteness with which they stand, light red, imposes ideas of durability, of the emergence through the earth of some spiritual energy elsewhere dissipated in elegant trifles”. My simple conclusion would be that Virginia Woolf’s own innovative modernist ‘marks’ – the sketches, near-episodes and glimpses of Jacob’s Room – offered a real sense of permanence in the fractured, ever fracturing world of 1922.

Dr Ruth McLoughlin, Teacher of English – Nicholson Lecture